24 February 2024

What does a trauma-informed approach look like in The Salvation Army?

Dr Claire Luscombe (Research and Development Unit) and Dawn Richardson (Thorndale Family Centre) share the positive impact of trauma-informed care with Stevie Hope.

What is trauma-informed care?

DR It’s about realising the prevalence of trauma in people’s lives, recognising how and when this might impact upon them, and how it might show up within their behaviours, communications, relationships, coping mechanisms and lifestyles, and responding appropriately in our support, services and interactions. Instead of judging behaviour, trauma-informed practice asks what’s going on.

We don’t ask: ‘What’s wrong with you?’ We ask: ‘What’s happened to you?’ Fundamentally, people must feel psychologically and emotionally safe. If they don’t, they’re unlikely to be able to engage positively in relationships and services. It’s compassion with a trauma-informed response that best meets people’s needs and supports their recovery. If I am safe, then I can love, I can experience belonging. This applies across our policies, practices and service provision – but to be meaningful organisationally, it needs to be systemic.

CL That’s why the Valuing People Framework is so important. Being trauma-informed is the engagement tool for creating healthy, flourishing and enabled environments.

Pick any one of our values and, without it, you couldn’t be trauma-informed. Compassion is central to it, though. Having curiosity to understand people’s lived experiences without blame or shame is compassionate ministry at its best.

What is trauma?

DR Some people consider trauma to be a car crash or war experiences. But it can be anything with significant, detrimental, long-lasting psychological impact. Frequently, it comes from the cumulation of negative experiences – violence, ruptured relationships, homelessness, marginalisation.

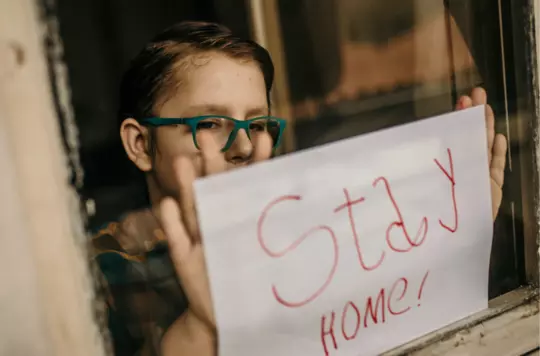

CL Trauma often stems from ‘Adverse Childhood Experiences’ (ACEs), which increase the likelihood of living with long-term consequences as adults.

How does trauma-informed care play out locally?

DR Once you’ve got the understanding, it’s about reflecting it across all expressions of mission within the organisation. This includes leadership, HR, training, finance, practices, programmes, places, protocols, communications and relationships among many more. The environment is a crucial element and can be a helpful place to start with. How do you ensure belonging, trustworthiness and collaboration from the minute someone comes into your space?

You bring me into a building that’s clinical and stark, where nobody knows who to speak to and posters are in a language I don’t understand and are potentially offensive or confusing to me. Do I feel like I belong here? Do I feel safe? We need to scan our environments, our waiting rooms, corridors, offices, halls. What message does this space give off? We must look through a trauma-informed lens and ask whether the space is trauma-reducing or trauma-inducing.

CL It’s all-encompassing. Do people immediately get a feeling of safety, or do they feel like you’re not interested? Critically, what will stop relationships from flourishing? The goal is to help someone feel safe with you so they can connect to you and engage with you.

DR We conducted a pilot within Mission Service where we completely reviewed the journey of a client and staff member from entry to exit through two services. We tried to understand every touch point and experience that a person goes through, to find situations where they might not feel safe. It was a very reflective process and it gave us time to think about things: we found that our welcome needed work, and I would ask people to think about that. If people don’t feel welcome, they will never feel safety or belonging.

CL And a welcome is not just the first time you meet, it’s every time you meet. For example, one of the services had barbed wire on its fence. As silly as that might sound, when you first come in and see that kind of thing, it’s not going to make you think: ‘Gosh, this feels like a safe place!’

DR Staff members said that they’d worked here for years and never noticed it because they were so used to it. So that’s what I mean: we really needed to take a step back and think through a trauma-informed lens about what’s in our environment and how this might impact upon individuals with lived experiences of trauma. We need to bring curiosity to every situation, wondering: what difference would it make to others if we did things differently here?

CL It’s a journey. There’s no end point. We all have to model the model. It’s all about being in this together.

Interview by

Stevie Hope

Editorial Assistant

Discover more

An online training course to equip leaders to help young people feel more resilient and cope with what life throws at them.

Human Resources Director Alex O’Hara talks to Major Julian Watchorn about how the Army’s values shape its policies.

Amy Quinn-Graham continues a series of articles reflecting on how our approach to mission has been affected by the pandemic.